Lay of the Land: A series of essays on the spirit of Montana

The Big Hole Valley is inextricably part of the family heritage — a distant relative ran his horses in its upper reaches; grandparents raised cattle on its lower stretches for decades. A high, wide riff that drains the snowpack from the peaks separating Montana and Idaho, it sources the longest river system in the United States. Although east of the divide geographically, the Big Hole River is nowhere close to Eastern Montana until the Missouri River meets the Musselshell at the Garfield County line on its way to filling Fort Peck Lake. Hunting waterfowl on the Big Hole River, one had to check the bag limits and season dates for the Central Flyway before shooting.

Ask the hay hands at Fetty’s Bar in Wisdom and they would all say that Billings is Eastern Montana. Ask the folks in Wibaux where Eastern Montana begins and ends and mostly likely they would say that the 16 counties west of the North Dakota state line constitute the eastern third of the fourth-largest state. The editor of the Last Best News once invited readers of the Billings Gazette to describe where Eastern Montana was located. An informed guess would be just past the Hysham Hills headed toward Miles City. Jordan is a sure bet.

Growing up in Western Montana, surrounded by majestic snow-covered peaks, blue-ribbon trout streams and lakes, vast wilderness areas and huge national forests, the thought of Prairie County as beautiful was the stretch of a perverted imagination. The Terry Badlands were yet to be savored.

Spoiled by the best fishing and hunting opportunities a young man could find, the peregrination to the U.S. Navy in San Diego and Seattle was a considerable jolt to my worldview. Thirty-days annual leave was taken each November for a junkie’s fix of elk camp and jump shooting ducks and geese off streams and ponds.

A return to resident status landed me in Missoula — the Garden City in every sense of the word. Potted plants grew well there and fishing on Rock Creek was legendary. Locals acknowledged little of consequence existing or occurring east of Hellgate Canyon.

Jobs for journalists in Montana in 1976 were limited in both quantity and recompense, but a “secret weapon” made it possible to remain under the Big Sky. A wife with an RN’s license prevented starvation while I worked my way up the newspaper ladder. First stop: Hill County. Not really Eastern Montana, yet the landscape foreshadowed what could be accurately described as the plains. Not much time was spent on them as a move to south-central Montana, where Billings and Yellowstone County actually are located, came after a stint of only 16 months.

As a new copy editor at the Gazette, responsible for the edition of the state news that went north and east, I was forced to learn where Eastern Montana was. A year later, assuming the job of state editor, my first trip into the outback was the beginning of a 30-year immersion in the people, places, landscapes and cultures of the Great Northern Plains. The Big Open, that vast grassland between the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, was representative. Its landscapes — recorded in the 1880s by L.A. Huffman, the frontier photographer of Miles City — retain their aura of solitude and serenity to the present.

No story of Montana can be told without a genuflection to the gods of weather. The plains get hammered by every variety and the stories they engender are endless. Floods, fires, droughts and blizzards provided this “westerner” with an introduction to hundreds of individuals whose lives and livelihoods were threatened by the vagaries of the climate at any time of year. Covering the state’s No. 1 natural resource industry — agriculture — brought that into stark focus.

Stark.

That one word describes Eastern Montana. As an adjective, it places accurate emphasis on every noun found in the verbal portrait of the hamlets and towns scattered across the map; most of them springing up with the coming of the railroads and the homesteader eras that marked the move toward statehood.

When Montana’s centennial was celebrated with a 60-mile cattle drive from Roundup to Billings over six days in 1989, it was the descendants of those pioneers who brought their finest horses and wagons to celebrate the survival of a culture that a majority in America knows little, or nothing, about. Roundup is where the cowboys gathered open-range cattle each year. The Musselshell River courses through the town and heads north to the Missouri forming the western boundary of the Big Open. Inordinate amounts of rain and runoff in recent years have brought damaging floods to Roundup, but during the extended drought cycles that began in the 1980s, the river was better known as a trickle. Fire has raked the Bull Mountains to its south during the dry spells.

The essence of Eastern Montana, bisected by the two great rivers, Missouri and Yellowstone, is grass. Although science has taught farmers how to harvest crops from land with no access to irrigation water, the Great Plains of America were created by the millennial migrations of vast herds of bison which grazed the grass, fertilized it with their waste, stirred up the soil and seeds and moved on. Bison, and their modern counterpart, cattle, are protein conversion machines that provided meat and everything else to the nomadic indigenous cultures that developed around them.

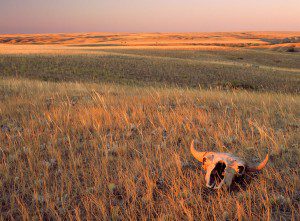

Just as “the West” is a state of mind, so too, Eastern Montana is a mental image. In a homage to the 20th century, Michael Malone, a historian of Montana and the West and former president of Montana State University at Bozeman, edited an anthology to celebrate the millennium — “Montana Century: 100 years in Pictures and Words.” In it, photographer John Lambing captured the stark beauty of the state’s plains as the setting sun cast long shadows and a golden glow across the prairie sealed with a bison skull like a Charley Russell painting.

There lies Eastern Montana.

Jim Gransbery is the retired political/agricultural reporter at the Billings Gazette. That combo for 24 years made sense in at least a couple of scenarios. Since 2008, Jim’s freelance work has appeared in Magic, Montana Magazine, the Montana Quarterly and Progressive Cattleman. He lives in Billings where his inherited dog, Sadie, takes him for a walk each day. He continues to look after the well-being of his wife, Karen, who made the journalistic journey possible.